Regenerative Farming; A Solution to Save our Soil

Agriculture in developed nations is consolidated around industrial, largescale farms. These farms, which will often grow a limited range of crops or even a single crop (also known as ‘monoculture’), are increasingly responsible for the food that we eat. The advantages of a largescale farm are commonly assumed to be self-evident: consistency of output and economies of scale. For the consumer in the supermarket, this translates to a reliable and consistent stalk of celery at an affordable price every time they shop. However, for industrial, large-scale farms to accomplish these advantages, they often employ techniques that are harmful to our biodiverse environment, health and contribute towards climate change. The real cost of our reliance on their products is revealed when their techniques are analysed over medium and longer time periods. A new generation of farmers and even the French government argue that this cost can be addressed and reversed by using simpler farming techniques referred to as ‘regenerative agriculture’, which operate on a more human scale.

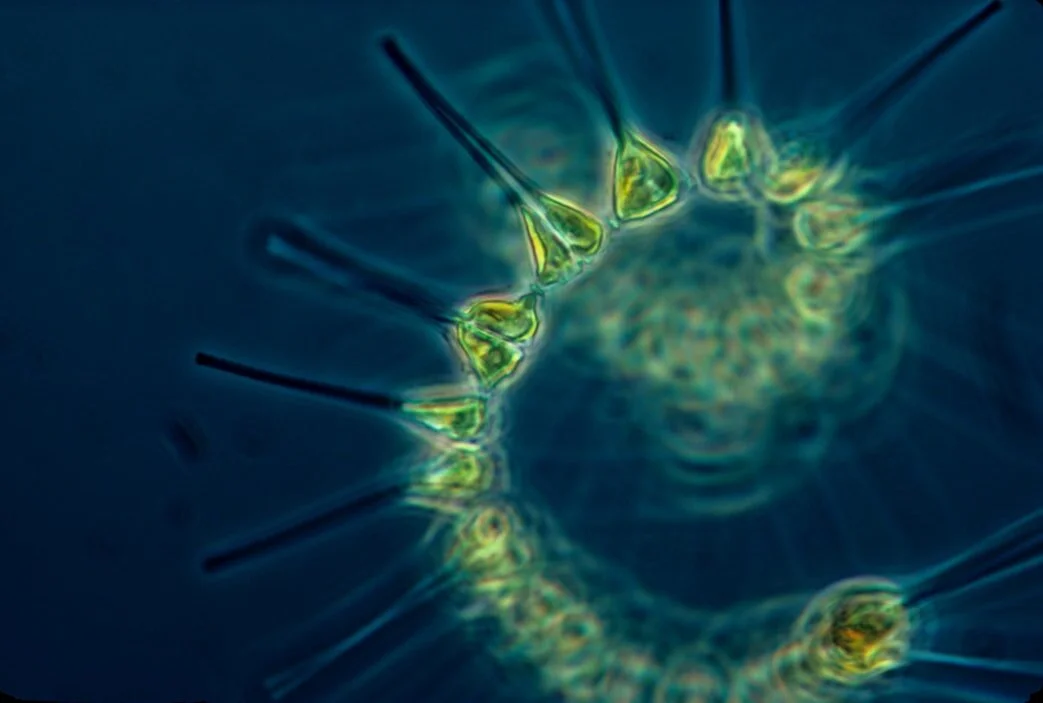

Most industrial, largescale farms operate with high tillage of the soil, which compacts it and leaves it bare. This depletes the soil of nutrients and its fertility. It also reduces the capacity for carbon to be absorbed and retained. To offset the problem of fertility, inorganic fertilisers (often derived from petroleum) and pesticides are used to maintain agricultural productivity. While these techniques have been successful in increasing the output per unit of land, their longer-term impacts are costly. Chemical fertiliser run off and pesticides disrupts our biodiversity and health, and requires the production of greenhouse gases in manufacturing, which contributes towards climate change. The tilled soil’s inability to absorb and retain carbon exacerbates this effect of climate change further.

"Soils are the basis of life," said Semedo, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations’ deputy director general of natural resources. "Ninety five percent of our food comes from the soil."

The lower cost of food items produced by intensive farming does not reflect, therefore, the full societal cost that it incurs. Much of the true, full cost is initially externalised from the producer and borne by others in society. However, these costs will eventually be internalised by landowners and farmers as top soil continues to degrade over time from these techniques and practices.

If top soil degradation continues at the current rate, farming only has 60 years of harvests left before the soil is unable to sustain crop growth.

These harmful techniques are also becomingly increasingly common in the developing world, as traditional (and of course organic) practices become replaced with similar techniques. Conditions in the Global South are already adversely exposed to the effects of climate change, with 24 million people globally displaced by the sudden onset of extreme weather events.

This cycle of top soil erosion, reliance on chemicals and climate change can be broken. Smaller-scale landowners and farmers have suggested that ‘regenerative farming’ practices could both end the negative cycle of large-scale intensive practices and reverse its impacts on soil. The basic principles are conservation tillage (little or no tillage, which compacts the soil and leaves it bare), diversity of crops, rotation and cover crops, and minimal chemical interference. Soil on farms that implement these practices increase the soil organic carbon (SOC). The French government launched the ‘4 per 1000’ initiative at the 2015 meeting of COP21. The initiative seeks to create an international co-operation on implementing this form of agriculture. Through this farming technique, soil can absorb greater levels of carbon from the atmosphere. With research supported by the French government, it is believed that the carbon levels held in the first 30-40cm of soil could be increased by 0.4% per year over the next three decades, significantly limiting the annual increase of carbon in the atmosphere.

If applied to all agricultural soils on Earth, the amount of sequestration could equal approximately 1-gigaton of CO2 or equivalent to £58 billion every year when accounting for the social cost of carbon. Of course, this does not take into account the added benefits of improving biodiversity and human health.

Implementation of regenerative agriculture has several barriers in the developed world: awareness among farmers, cost (incentives from government subsidies can misalign with the aims of regenerative agriculture) and access to manure. However, its potential to sequester carbon is far more efficient than mechanical carbon capture systems in terms of cost and energy. Making it one solution which will help close the 11-gigaton greenhouse gas (GHG) gap between agricultures expected emissions in 2050 and the target level needed to hold global warming below 2°C.

Route2 delivers unique insights into the total impact of business activities. We offer businesses expert advice and analysis about historical and future performance. Our services (coined Value2Society) strengthen decision making, establish competitive advantage and enhance the value business delivers to society.

To find out more, email us at info@route2.com or phone +44 (0) 208 878 3941

Follow our social media to never miss a post: